REGENERATIVE AGRICULTURE CASE STUDY

PARTNERING FARM ANIMALS TO REGENERATE THE LAND

GO TO:

FARM FACTS | INTRODUCTION | PROPERTY BACKGROUND | CHANGING PRACTICES | SOIL MANAGEMENT | WATER MANAGEMENT | VEGETATION MANAGEMENT | PRODUCTION | OUTCOMES

FARM FACTS

ENTERPRISE: Sheep, cattle.

Fine (16 micron) merino wool; Merino cross Samm cross white Suffolk fat lambs; cross-bred first cross Hereford/Gelbvieh dams joined to composite (Devon/Angus/Simmenthal) bulls producing steers to 400kg

PROPERTY SIZE: 3350 hectares (also Kasamanca 780 hectares, 50km east)

AVERAGE ANNUAL RAINFALL: 769 mm

ELEVATION: 800-1000 m

MOTIVATION FOR CHANGE

- Excessively high costs of production and the opportunity to better use the grazing animal

INNOVATIONS

- Holistic Management against 10 key principles

- Time-controlled rotational grazing using stock for nutrient movement, enhancing soil fertility and vegetation management

- Innovations commenced: 1990

KEY RESULTS

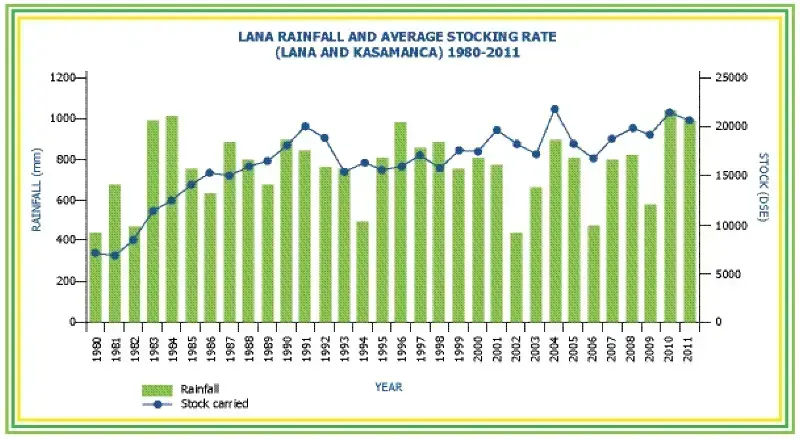

- Carrying capacity increased from 8,000 to 20,000 DSE, even through reduced rainfall and drought

- Wool quality improvement in strength and micron

- Increased lambing and calving rates

- Reduced labour requirements from one person per 5,000 DSE to one per 12,000 DSE

INTRODUCTION

The 1990s were a crisis period for Australian agriculture, marked by excessively high production costs and falling profits. The 1990s also brought a realisation for Tim and Karen Wright that they needed to look for a better way to manage their farm. They had an insight that their stock could be used more effectively to provide more than just a source of income. This led to gradual changes across their properties, guided by their own principles for ‘Working with Nature’. After a considerable journey of reading and research, the Wrights were motivated to fully adopt a Holistic Management approach for operation of Lana and Kasamanca.

Principles and practices of Holistic Management were introduced to the Wright’s properties, including establishing smaller paddocks and rotational grazing of their sheep and cattle. Pasture availability now drives stocking levels and rate of rotation. Pastures are heavily grazed for short periods, but for the majority of the time are in recovery phase. A leader-follower system is used, grazing cattle followed by sheep, to maximise pasture availability. Fences have been orientated with contours to facilitate nutrient movement from high ground sheep camps to across the slope. Soil organic matter content and fertility have been improved by this grazing action and the interaction of livestock nutrient deposits with soil biology.

For the Wrights, their grazing practices have driven fertility, which has increased pasture availability and quality, improving production – even with reduced rainfall and during times of drought. Together with their livestock, Tim and Karen Wright have regenerated their property, and their lifestyle.

ADOPTING HOLISTIC MANAGEMENT PRINCIPLES

Lana comprises 3350 hectares of moderately treed granite slopes and open riparian zones adjoining two major creeks forming part of the Gwydir River catchment. Tim took over the property from his father, Peter, in 1980, who had farmed it since 1952.

Various strategies of pasture improvement had been used on the property in the past. In 1960, approximately 20% of the property was top-dressed and sown with improved pasture. Later, the whole property was top-dressed with superphosphate and seeded from the air. Oat fodder crops were under-sown with various pasture species, and this pasture improvement enabled stock numbers to be more than doubled between 1981 and 1992.

However, with the expensive inputs, the property barely broke even over a five year cycle. In the 1981 and 1992 droughts, production records revealed that the improved paddocks had lower yields than the unimproved paddocks. The land was too susceptible to drought and profit margins were falling. It made sense to seek a change.

Tim recalls, “In 1990 we were motivated by two key considerations to decide what and how we should change. These were the excessively high cost of production, especially labour, but other inputs as well, and the opportunity for better use of the grazing animal within grazing management”.

It was adopting a Holistic Management approach and undertaking both the Holistic Management and Grazing for Profit courses that ultimately made a huge impact and influenced the Wright’s decision-making. They learned that, “Holistic Management is about ‘thinking’; about cause and effect, about weak links and risk management, about testing concepts and ideas against our holistic goal”.

Subsequently, Tim and Karen developed ten principles, which they call ‘Working with Nature’, to guide their farm operations. All of their management decisions are tested against the ten principles. If the decisions do not align, they are reviewed. “We assume we could be wrong. For example, we ask ourselves if we are targeting the weakest link in the production chain, and whether we’re treating the cause or simply a symptom.”

WORKING WITH NATURE

Develop a holistic goal that considers personal values, natural resource base and available finances.

Match the enterprise to the environment, not the other way around.

Match the stocking rate to the assessed carrying capacity of the land and revise assessments frequently.

Manage for the full range of plant species and the whole ecosystem.

Think of livestock as tools.

Design paddocks to suit the topography and the land.

Use a flexible grazing plan and monitor the water and mineral cycles, energy flow, and the plant sward to ensure the plan is on track.

Supplement stock with minerals but not feed substitutes.

Test all decisions against the holistic goal.

The highest return on capital comes from education, not regulation. What looks good in the paddock is not necessarily good on the balance sheet.

IMPLEMENTING CHANGE

Following their ten principles, the Wrights experimented with cell grazing between 1991 and 1993 and were encouraged by outcomes to move fully to planned grazing in 1995, combining both Holistic Management and cell grazing principles.

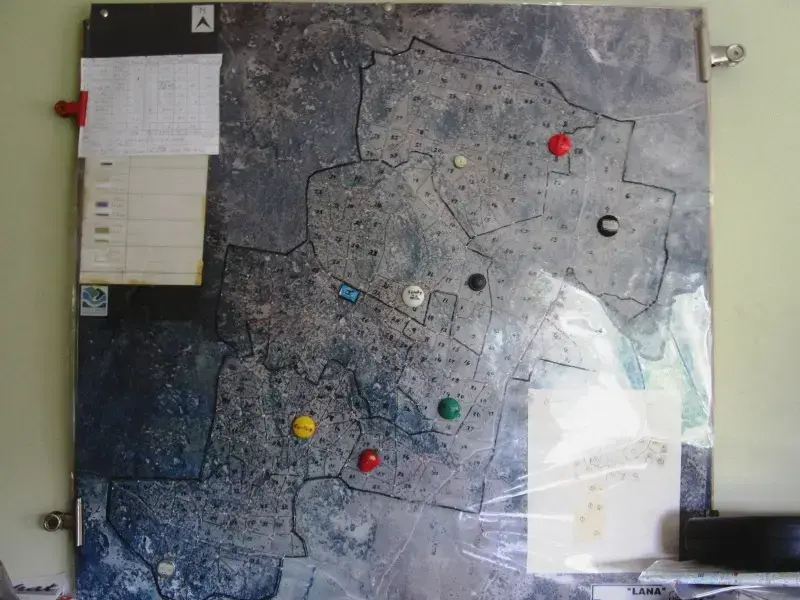

FENCING

In 1980 Lana was originally subdivided into 30 paddocks of generally 100-120 hectares, with varying grazing areas. Since 1990 these have increased to 350 paddocks, averaging 10-15 hectares. Paddock size is seen as crucial to effectively use available pasture in relation to stock density and the stocking rate, which are adjusted accordingly.

Tim describes, “We fenced on contours to prevent sheep camps from developing on high ground and to spread nutrients laterally and more evenly”.

Permanent fences at approximately $400 a hectare were installed using steel, and, Tim explains, “We built our own steel end assemblies. We do not use our own timber for on-farm use because, as well as the trees being useful where they are, the cost of labour to cut posts and clear up debris exceeds the cost of buying steel end assemblies”.

Each subdivision required about three quarters of a kilometre of fencing, costing about $800 per kilometre at the time. More recent costs are closer to $1500 a kilometre. Tim found that two men could build one kilometre of fencing in a day. The bulk of the fencing was built over 15 years and there are plans for further subdivision to better manage the availability of pasture. Tim says, “It is important to note that the cost of development is returned within two years”.

WATER

Heavily eroded watercourses were fenced off and weirs constructed to stop head-wall erosion and divert water from watercourses onto the flood plains. Wetland plant species were established in all watercourses and weirs. Tim notes, “Stream bank erosion is healed and the old irrigation dam is now like an artificial wetland, with reed beds and fringing dense cover”.

Creeks and dams were initially relied on for stock water, with dams fed by aquifers and clean runoff. A tank and trough system was constructed to supply water to the new paddocks. Watering with a trough system required installation of 3.5km of 50mm pipe from one end of the property to the other, mainly using gravity feed from dams built high in the catchment and, in some cases, by pumping from creeks to header tanks on high ground. Tim notes, “We don’t need troughs in wet seasons, but they are a good drought standby. A mix of dams and troughs gives us the best of both worlds”.

The stock watering system ensures that the stock are provided with clean water. Tim points out, “Troughs are good for a leader-follower system where the cattle disturb the dam water. Nebraska Feedlot research has shown that cattle do better on clean water; stock can lose half a kilogram per day on muddy water in a dam. Now the stock are no longer around water courses long enough to damage them and they always have a clean water supply. We also no longer get dung around the dams nor as many nutrients ending up in the water”.

FINANCING

The new fencing was initially funded by reducing other costs, such as fertiliser and hay, and abandoning pasture renovation. Tim achieved return on his capital investment in two years, particularly through significant reduction of vegetable matter in the wool. Vegetable matter in skirtings has reduced from 9% to 2% since 1982, enabling Tim and Karen to decrease the amount of skirtings, increasing the main fleece lines and subsequently the overall value of the wool clip.

Increased production through the ability to raise stocking rates has also covered financing of fencing and water infrastructure.

The properties now carry 7000 sheep and 700 breeding cows at a stocking rate of 5 DSE* a hectare in winter and 7-8 DSE a hectare in summer. This is without feeding hay or grain – only using Himalayan Salt and occasionally Bypass Protein Supplement, such as Cotton Seed or Coprameal during drought times.

EDUCATION

Tim and Karen believe that innovative farming cannot be done without knowledge and skills development and an understanding of how the land ‘works’. Their investment in knowledge growth, development of skills and the benefits of continuing experience has been necessary for successful innovation in their farming operations.

We manage under the holistic thinking that we assume we could be wrong, and we monitor and replan.

Tim comments, “There is always a certain amount of pressure arising from ingrained attitudes among farmers, academics and bureaucrats, that are resistant to change. Some farmers continue to manage their production cycles irrespective of the long-term effects on farm landscape. Some academics are tied to the knowledge and literature of the past and some bureaucrats are tied to outdated policies and regulations. There were times when many people thought we were stupid”.

“We have received minimal support from government entities, particularly NSW Department of Primary Industry officials, and some scepticism from academics. That is gradually changing as newer thinking takes hold. Training and education are essential at all levels to change attitudes. We manage under the holistic thinking that we assume we could be wrong, and we monitor and replan. This is the holistic feedback loop, which is really important. Tomorrow is another day – nature is changing every minute and we have to change with Mother Nature, and this includes climate change.”

Both Tim and Karen continue to read and research and seek mutual support from others going through similar processes. They host regular field days and visiting speakers to the property, provide mentoring to other landholders and maintain an ongoing relationship with the University of New England. They believe that all education provides high return on investment.

LIVESTOCK AS FARM TOOLS

It was the understanding that grazing management needed to change to better use the grazing animal that led the Wrights to develop their fifth principle, ‘think of livestock as tools’. They recognised that stock could be used to transfer nutrients off sheep camps, reduce weeds and intestinal worm infection; in effect, be used as the farm machinery for slashing, fertilising, sowing and managing pasture. Tim emphasises, “Stock density, the herd effect, and planned rest from grazing are as much tools as is a plough”.

“We use the farm livestock as the tools to enhance the land as well as their being a source of income. The slasher in their teeth, the plough in their feet and the fertiliser equipment in the rear. Animals distribute nutrients across the grazed areas and build soil. Earthworms, dung beetles and other soil builders are critical to the development of healthy soil. ”

Planned grazing based on Holistic Management guidelines involves intensive grazing with a high stock density for short graze periods followed by long rest periods. Tim reiterates that they now “manage the whole ecosystem, using the livestock as ‘tools’ – no conventional farming methods are practised. We use ‘strategic rest from grazing’ to enhance the environment. At any one time, 95% of the property is in recovery mode”.

Each paddock gets an average of eight to ten days grazing per annum, or two to three days grazing in each season. Livestock are moved more rapidly during fast pasture growth and less rapidly during slow growth periods, for example, winter or times of drought. No hay or grain has been fed to the livestock since 1990, and Tim notes, “We were only using mineral and bypass protein supplements, as of 2010 we are only using Himalayan salt”.

Cattle and sheep on Lana are grazed separately in a ‘leader-follower’ system. Cattle are grazed first for two days, opening up the pasture for the sheep and reducing the worm burden. Sheep then follow for two days. Intestinal parasite cycles have been broken by rotational grazing. With the flexibility provided, cattle are sometimes grazed with the sheep to stop the cattle getting too fat and to reduce the risk of bloat if there is too much clover. A ‘split-leader’ system is also used on occasion, for example, with calf heifers first or for fattening special stock for market.

Pastures are now altered by using grazing management and no chemicals are used. Tim notes, “Chemical fertiliser has not been applied for the past five years, yet our carrying capacity is slowly increasing due largely to the improved biological activity in the granite soils”. Close monitoring of the different species determines what and when and how to graze a paddock. Tim aims for one-third of the pasture to be eaten, one-third trampled, and one-third left for recovery.

Tim illustrates, “We do not sow in any conventional sense. Our animals spread the seed through dung and the increasing fertility of the soil becomes an ever improving seed bed”. The growing availability of pasture is driving further subdivision of paddocks to ensure correct grazing pressure and avoid pasture becoming rank from under-utilisation. The most productive area on Lana has an average of four hectares per paddock, with an average stocking rate of 20 DSE per hectare and density of up to 500-600 DSE per hectare. Tim believes that, “The productivity is largely due to the smaller paddock size resulting in improved soil biological activity due to greater animal impact”.

The productivity is largely due to the smaller paddock size resulting in improved soil biological activity due to greater animal impact.

The stock provide all the ‘farming’ required to maintain and enhance pasture and the soil. “We focus on having 100 per cent ground cover 100 per cent of the time so that soil is always protected. Litter is money in the bank. Softer soils attract fertility and generate regrowth. We rely on an increasing variety of native pastures to provide carrying capacity all year round. We rely on the stock to manage the fertility of soils and the availability of pasture.”

The cattle breeding herd on Lana now comprises 70% spring calving and 30% autumn calving. As Tim points out, “The increase in cool season native perennial grasses has resulted in improved native pasture growth to allow more nutritional pastures during the winter”.

The grazing operations have had a positive impact on watercourses, riparian zones, dams and wetlands. There is no erosion of stream banks. Regeneration of vegetation in riparian zones is increasing from natural seeding. Water quality is high and dam levels are maintained from soil hydrology well after rainfall event runoff ceases. This is due largely to the effects of adopting a holistic grazing plan, resulting in an improved water and mineral cycle, community dynamics and sunlight conversion. The Wrights consider these their four foundation blocks.

SOIL & VEGETATION

Soils across Lana are well-drained coarse and fine granites. In the 1990s, Christine Jones from the Botany Department of the University of New England helped look at the mineral cycle during grazing trials being performed. A four to five times increase in available phosphorus was found in areas that hadn’t been fertilised over a three year period, along with increases in total nitrogen and potassium. The findings confirmed that the Wrights were on the right track, as the soil health was due to:

- the rest factor – the pasture roots were growing deeper, drawing up the previously unavailable nutrients;

- the pasture was in recovery phase 95% of the time, meaning more litter is being laid down, enriching the topsoil with organic matter and building soil organic carbon without additional artificial fertilisers; and

- the transfer of nutrients off the sheep camps. It takes about ten days for nutrients to pass through the animal, and by moving stock every two to three days, nutrients were being passed into a number of other paddocks.

Prior to farming, the land was open native grass woodland with Blakely’s red gum (Eucalyptus blakelyi), yellow box (Eucalyptus melliodora), white box (Eucalyptus albens), rough-barked apple (Angophora floribunda), apple box (Eucalyptus bridgesiana), stringybark (Eucalyptus caliginosa) and mountain gum (Eucalyptus dalrympleana). In contrast to earlier management practices, timber regrowth is now welcomed and encouraged. About one third of Lana is timbered. Trees provide shelter in hot and cold weather and the mild temperatures in tree belts shelter some species of grass in winter. Trees also support wildlife and species diversity. Kangaroos are widespread and there are wallabies in the hills. Koalas have been observed in some areas, as well as brush tailed possums and sugar gliders. The property also has numerous species of birds, including water birds, and platypus and water rats inhabit a number of creeks. Lana has been a gazetted wildlife refuge since the 1960s.

“Trees are an integral part of our ground cover and of our ecology. We encourage tree growth to extend shelter corridors and to provide habitat for wildlife. Seedlings come from natural seeding and survive because of the low impact on seedlings from rotational grazing. If there is over production of some species in a particular area, selective thinning may be required, but this is rare.”

Pastures are no longer sown, and the property is managed for biodiversity, particularly of native species.

Trees are an integral part of our ground cover and of our ecology.

In terms of pasture variety, there is some vestigial sub-clover, phalaris and fescue from previous improved pastures that survived the drought. Lana receives an average annual rainfall of 769mm, though an all-time low of 397mm was experienced in the drought of 2002. No hay or grain needed to be fed during that period. Overwhelmingly, native pastures now dominate, with a continuing variety of species regenerating. Natives, such as weeping rice grass (Microlaena stipoides), crowd out not only weeds, but also remnant exotics.

Prior to present management, saffron thistles (Carthamus lanatus), blackberries (Rubus fruticosus) and briars were commonplace. Large quantities of herbicides were used to control these. Chemical spraying of thistles was stopped around 15 years ago, and with the introduction of rotational grazing and other innovations, there has been no major weed problem for the last ten years.

In the 1990s, Tim had originally tried pasture cropping, but, with the increased ground cover from the native pastures, the operation was not viable, and, in due course, the need for a pasture crop was overtaken by adequate winter pasture from native species. It was an activity worth trying, but was ultimately not necessary to achieve the desired outcomes.

NOW & BEYOND

Change requires knowledge and understanding. We hope that all land managers will one day appreciate the need for life-long learning and demonstrate an awareness of the importance of sustainable land management.

On Lana and Kasamanca, Tim and Karen have focussed on having their grazing practices drive fertility. “Fertility drives pasture availability. Pasture availability drives production. Stocking rates have improved steadily and continuously, even during drought. We have also managed to diversify and widen production lines.”

Since adopting Holistic Management practices, their production, workload and lifestyle has changed. Production has increased and inputs have decreased.

On average, carrying capacity has increased from around 8000 DSE to 20,000 DSE. Management practices have improved the natural resource to such an extent that this has been possible even through reduced rainfall and period of drought.

Production improvements have seen wool staple strength increasing from an average 40 N/Ktx (Newtons per kilotext) to 48 N/Ktx. Average fibre diameter has improved from 17.5 micron to 16 micron. Merino lambing has increased from 80% to 90% and quality is improving allowing Lana to produce 1st and 2nd cross prime lambs. Calving rate has also increased from 80% to 90%, most likely due to the improved nutritional value of the stock feed.

Over the last ten years, permanent labour requirements on the farm have reduced from one person per 5,000 DSE to one person per 12,000 DSE. Tim and Karen have more time for family and off-farm social, community and consulting activities. Labour is less intense except for key periods such as lambing and shearing.

“We can be, and are, involved in off farm activities to a greater extent, but we must cover the need to open and close gates to rotate stock and we must be here for key activities like lambing.”

Overall, the Wrights believe that successful farmers must have a flexible grazing plan to support long term management of pastures, livestock, biodiversity and personal wellbeing. “‘There is a need to read, consult and understand how the pieces of the grazing plan come together. Define goals, decide on actions, identify weak links, manage risk, and be prepared to change if things don’t work out. Everything is connected to everything else.”

“The threat of drought is always with us and we must plan that into our farming strategies. Old ideas of drought subsidies are not sustainable. Farmers must manage the impact of drought on their businesses.”

The Wrights also believe that there should be incremental, modular certificate and diploma courses in applied farming techniques aimed at working farmers at University of New England and other agricultural campuses. They believe that this training could be sponsored by Landcare and the federal Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry.

Farmers talking to farmers and sharing knowledge and experience is also seen as vital to spreading better practice in farming.

Tim and Karen understand that everyone has their own situation, but feel that their model can be broadly applied, “We have ten principles that underpin our Holistic Management strategy. Our principles work for us, but they may not suit everyone. It depends on your own holistic goal and the resource base you are dealing with. We test all our decisions against the holistic goal. If the test fails, the decision is faulty”.

“Change requires knowledge and understanding. We hope that all land managers will one day appreciate the need for life-long learning and demonstrate an awareness of the importance of sustainable land management. This would help reduce the burden of extensive regulation and legislation for future generations.”

Reference: Southern New England Landcare Ltd (2005) Land Water & Wool Case Study: Tim and Karen Wright working for Wool production and biodiversity. Land and Water Australia, Canberra, ACT. http://lwa.gov.au/